The Munich Lectures in Ethics 2019

Philip Kitcher on "Moral Progress"

Overview

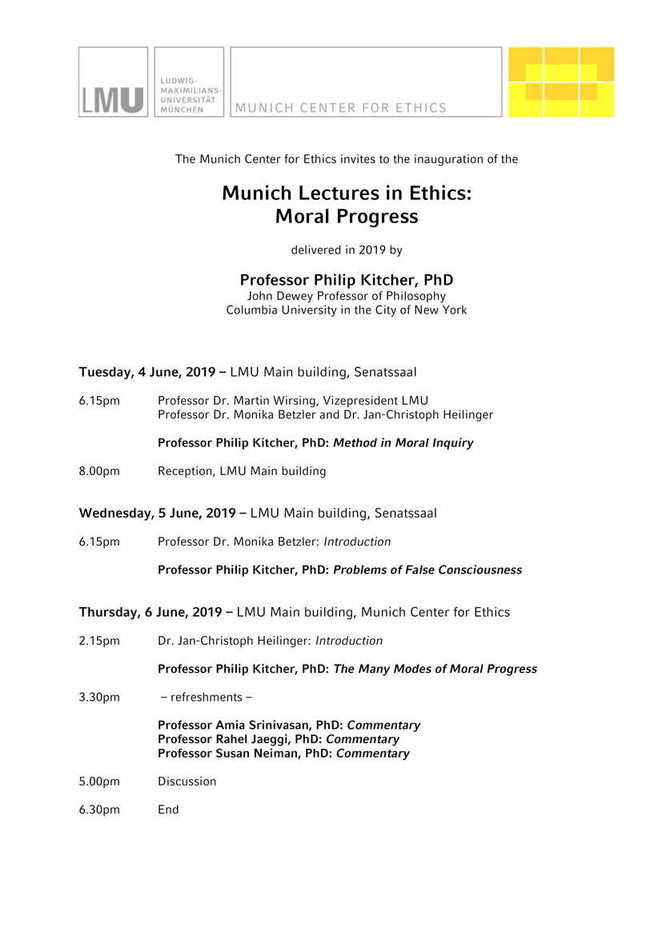

The Munich Lectures in Ethics consist of three lectures, delivered by Philip Kitcher, John Dewey Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, New York, on the topic of “Moral Progress”. An international workshop with professors Amia Srinivasan (University of Oxford), Susan Neiman (Einstein Forum Potsdam) and Rahel Jaeggi (Humbold University Berlin) will follow the lectures.

Seating is limited, please register here.

Organised by Monika Betzler and Jan-Christoph Heilinger. Contact: mke@lmu.de.

Dates

| Time | Title of the Lecuture | Room | Lecturer(s) |

|

4 June 2019, 6.15 - 8 pm |

"Method in Moral Inquiry" (Lecture) |

Room E 110 (Senatssaal) |

Philip Kitcher |

|

5 June 2019, 6.15 - 8 pm |

"Problems of False Consciousness" (Lecture) |

Room E 110 (Senatssaal) |

Philip Kitcher |

|

6 June 2019, 2.15 pm |

"The many modes of moral progress" (Lecture and Workshop) |

(MKE) |

Rahel Jaeggi, Philip Kitcher, Susan Neiman, Amia Srinivasan

|

Abstract: On Moral Progress

2019 Munich Lectures in Ethics

Munich Centre for Ethics, LMU Munich, 4-6 June 2019

Professor Philip Kitcher, PhD (Columbia University in the City of New York)

The lectures will aim to develop a new account of moral progress. Some people deny that the notion of moral progress makes coherent sense. Those more sympathetic to the idea often propose that moral progress occurs when groups of people (typically societies) replace false moral beliefs with beliefs that are closer to the truth. Their guiding conception relies on a domain of prior moral truths whose character is disclosed as moral inquiry makes progress.

The approach presented in the lectures will break with these dominant views in a number of different ways. It starts by recognizing that individuals, as well as societies, can make moral progress. Moreover, the progress of individuals is dependent on and contributes to the progress of the societies to which they belong. Progress is also not simply a matter of moving from an unfortunate cognitive state to a better one. Moral beliefs are constituents of moral practices – complex entities that involve dispositions to act, to suspend action, to begin reflection, to consolidate

patterns of behavior as habits, and so forth. Finally, there is no realm of prior moral truths that progressive individuals and progressive societies discover. Rather, moral truth emerges as we make moral progress. The moral truths are the stable elements of indefinitely progressive moral traditions.

Behind this account stands a recognition of two modes of progress. A common mistake is to suppose that all progress must be teleological: progress is measured by decreasing distance to some long-term goal. In many areas, however, progress consists in moving from a problematic situation through a partial solution of the problem. As I shall try to show, elaborating the concept of “progress-from” in the context of morality involves tackling some delicate questions – What exactly counts as a problem? How are problems recognized? What counts as a solution? The lectures will explain why these questions matter, why they are difficult, and how they are overcome.

Some of the most striking candidates for morally progressive changes involve the abolition of slavery, the expansion of opportunities for women, acceptance of same-sex love, and protections for non-human animals. Each of these examples reveals changes in beliefs, in emotions, in heightened moral sensitivity, and in patterns of behavior. Yet if progress consists in overcoming problems, it’s important to ask just what made the prior state of affairs problematic. Surely, for many people who lived under the antecedent conditions, that state wasn’t seen as problematic. A philosophical account of the kind envisaged in the lectures thus requires explaining how a situation can embody a problem without that problem being widely recognized – and also how general agreement on the existence of a problem may be mistaken.

To suppose that we can make sense of moral progress does not entail any view about how frequently moral progress occurs in human history. But Kitcher shares with John Dewey the thought that our species has sometimes made some moral progress, and that such progress has typically been blind and the product of happy contingencies. Indeed, the episodes he heralds as “progressive” could easily have turned out differently. Like Dewey, Kitcher takes a clear understanding of moral progress to be a first step in making moral life more “intelligent” and in increasing the frequency with which moral progress occurs. The lectures are thus an attempt to revive significant parts of Deweyan pragmatism.